My partner and I first contacted the VoSNL with our vision, after receiving the organization’s support and access to its myriad of experiments, we got to work. We began to write the script for a pilot episode we would pitch at the Hospital for Sick Children. We submitted our script to the Event’s Organizer at the hospital and we were invited to perform a few days later. Materials and costumes were purchased and we soon found that we would require external financial support as the start-up costs were quite hefty. We performed our first episode and were soon invited back. We perform biweekly as part of the SickKids Television Network (a hospital wide TV network).

Our program uses skits as a means of promoting scientific awareness that is both informative and comical. Each hour long skit revolves around a central theme (i.e. “The Environment and Conservation”) during which time 3-4 experiments are conducted. Each experiment examines a different aspect of the theme (i.e. paper-making and windmill experiments pertaining to the Environment and Conservation). The theme of each episode is based on questions we receive from an evaluation form handed out to the audience after every show. Each experiment involves a different set of child-friendly personalities (i.e. Disney characters) appearing as guests to explain various scientific concepts. Two characters, a mad scientist and an inquisitive little girl, functioning as hosts will provide a level of continuity, appearing each episode. The experiments are conducted in a way that is both engaging (audience participation) and comedic.These experiments provide therapeutic value as they act as a means of escape from the busy and often unsettling hospital environment.

Success was measured via evaluation forms, as well as feedback from care-professionals and nurses regarding patient interest. Evaluation forms were filled out by patients after every show. This allowed us to quantify audience turn-out, measure performance, and acquire questions for the subsequent week's episode.

Although, I had volunteered in the past--I had never created my own volunteer cause and was accustomed to working under someone else's supervision. As a result, I had no idea of the great time and dedication that would be required to make our vision a success. However, it was through this process I gained a greater respect for NGO that are often created by a single person or group of persons who share a common dream, and the struggle required to have these ambitions materialize. I learned of the bureaucracy that must be navigated to achieve one's ultimate goal, particularly in large organisations and the persistence and time required to create a meager ripple that would resonate through all levels of the governing body (nurses, doctors, CEO, etc). Finally, I learned to communicate with individuals in a dignified and mature manner which has allowed me to network and gain greater insight into existing opportunities, and will surely aid me in my future endeavours as this is a quality that is invaluable.

Placement Coordinator: Caron Irwin

Caron Irwin is a Child Specialist at the Hospital for Sick Children. Her current position is that of Development Officer. Child Life Specialists are paediatric health-care professionals. They work together with child-patients, their families, and all those involved in the child's care in order to help manage the stress involved with the hospitalization process and the rift it may create in familial relationships--this is done through education and various other means designed to reduce anxiety (i.e. organizing events, play, games, learning, etc).

Upon entering Sick Kids, I did not realise the grandiose nature of the task Bushra and I had sought out to accomplish. It had not hit me that we had become a part of the world's greatest and most renowned paediatric hospital. However, the first thing I did realise was the selflessness and humble nature of the staff members (be that caretakers, nurses, or medical doctors). Ms. Susie Petro who had first been assigned to be our coordinator (Ms. Irwin had been away on maternity leave) was very encouraging, she was a very jovial young woman and continuously reviewed our pilot script and provided us with whatever the hospital could provide us in terms of materials. I must admit, Ms. Petro had been one of the sweetest people either Bushra or I had ever had the pleasure of working with. As a result, when news came that Ms. Irwin had returned and that Ms. Petro would no longer be overseeing our operation, Bushra and I began to feel quite anxious. However, Ms. Irwin was nothing short of amazing. She showed us continual support and gave us further guidance, making the transition between coordinators a smooth one. Ms. Irwin continued to encourage us to "dream bigger" and think about making our project a greater part of the hospital and shared our vision of producing a more science-literate patient populace. These two women truly embody the essence of Sick Kids, one of greatness while maintaining an unassuming quality that allows all to feel welcome--surely the 2 key attributes that has allowed SickKids to rise above all other hospitals and achieve unprecedented levels of greatness.

Hierarchy of SickKids (Road Map)

This is simply a schematic that shows where Bushra and I fit in the whole scheme of things. Sick Kids is an integrated system involving both quality of service and child health care. As you can see these two major subdivisions are under the oversight of the Hospital Director and Board of Trustees—they ensure that the hospital deliver world-class service. The quality and service subdivions can be further divided into child-life specialists and support groups, whereas the child health care group can be divided into researchers and health care professionals. It is through these individuals the hospital creates a culture of service excellence. Bushra and I fit somewhere in between the child-health specialists and support groups by providing catharsis through learning and play. We are similar to the child life specialists in the sense that we aid in the process of socialization, expression of emotions, and normalization and learning—but we also provide a setting that promotes a form of interaction amongst the children—and may function more like group therapy in certain respects.

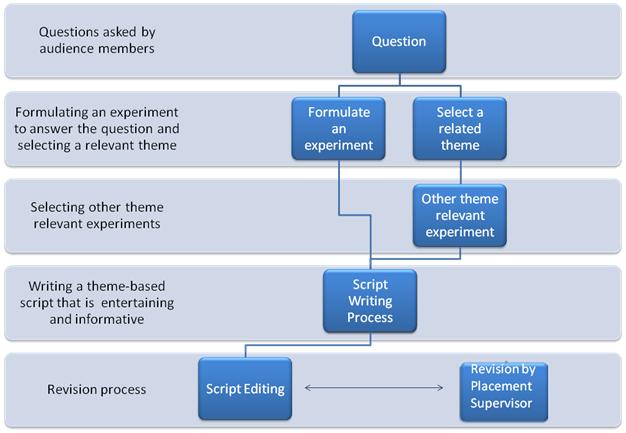

A Single Episode the Process

This a diagramatic representation of the process involved in each episode and highlights my responsibilities. Both Bushra and I would select an appropriate question that we could agree would provide a realistic experiment and prove to be a valuable learning experience. We then began to carry out the script writing process (elucidated further below). We would send the first draft to Sick Kids where it would be refined, we would make the appropraite alterations and have it reviewed again--this occurred in a cyclic pattern as outlined above until we arrived at our final product. As one can imagine this was a very lengthy process and proved to be quite cumbersome at times. While this editing took place, we would begin to acquire themed costumes and would begin to buy our experimental materials in anticipation of our presentation. We would also begin to put together the activity sheets that corresponded to our experiment for the children--handed out prior to our show as place-mats for adverstisement as well as after our show as a souvenir. When we finally acquired the final script we would begin practicing with our test audience (as mentioned in my journal entries--this consisted of family members that fit the age range of our target audience). We would often recieve our final edit approximately a day or two prior to presentation--thus leaving very little prep time (on top of school and extracurricular responsibilities). On presentation day--everything was a go and we were on most occassions received gleefully by our young fans--making all the stress and labour worthwhile.

Script Writing Process

The flow chart above describes the process by which Eureka Science scripts were generated. It was quite a lengthy process and required a three week period—one week allotted to question-related research and script writing. Questions were produced by individuals in the audience (those viewing the show in their rooms, as well as individuals within the live audience).The questions were retrieved via an evaluation form sent out to all those viewing the show and interested in providing feedback. Thus, the evaluation form served a dual purpose—it provided us with constructive criticism, as well as questions from audience members. The questions were used as a centerpiece on which the show’s content and theme were based. After producing an appropriate experiment to answer the question, a theme related to the original question posed was selected. The theme was then used to create 2-3 other related experiments. The experiments were all amalgamated within a single script that would hopefully explain, in detail, the questions riddling our young viewers, in a manner that was both interactive and comical. Scripts underwent a strenuous and extensive script editing process—approximately 2 weeks were allotted to editing. ‘Script Editing’ entailed presenting the script to individuals (family members) who fit the age demographic of our target audience (4-12 years of age). Suggestions were used to make the appropriate alterations to our script and the first complete draft was sent to our placement supervisor for further revision. Advice regarding further improvement from the placement supervisor was used to make the final modifications to our script and produce a finished product.

This process has provided a great learning opportunity in many respects. Bushra and I were forced to conjure up ideas that would best illustrate the questions we had been asked by the children and then determine whether they would work based on trial and error. Although at first very time consuming, this process became more efficient as we learned to conceptualize outcomes using scientific principles we had learned in class and through life experience. We were forced to research topics, often very fundamental scientific theory, and understand the true grit of the material and then formulate our experiments based on our improved understanding. This made the experimentation-formulation process occur more efficiently and with greater fluidity. This also provided ample opportunity for Bushra and I to disagree of course. We often did not see eye-to-eye on various forms of presentation and experimentation--although at first we both were quite set in our ways we gradually learned to compromise and incorporate ideas from both parties. This resulted in the best results and the most interesting episodes. Finally, I learned to accept constructive criticism, which proved to be in abundance particularly during our first couple of shows. Sick Kid's had provided us with an on-site teacher who watched our first show post the pilot (perhaps our worst show) and provided us with a great deal of feedback. As one can appreciate, after undergoing this lengthy script writing, acting, editing, and experimentation process--we had become quite attached to our work. I began to associate myself very strongly with our finished product and, quite immaturely, began to view the criticism towards my work to be a direct criticism of me as a scientist and presenter. However, after grudgingly following the advice provided, I found that our presentation was better received by our audience making the entire process more enjoyable. I began to understand the significance of a few words of wisdom and the great impact they could have overall on our presentation, as well as me as a person.

Audience

Our audience consists of hospitalized children between the ages of 4 and 12. Toronto is becoming an increasing multicultural society, with 50% of the total population being immigrants and 36% speaking English as a second language. Sadly, approximately 10% of all children live below the poverty line in Toronto, and this proportion of children isoverrepresented in hospital settings like SickKids due to increased exposure to things such as poor living conditions, malnutrition, etc. Due to their living conditions and fiscal state, these children may not have the appropriate level of parental support to fully reach their potential in the realm of academia, even though they may harbour a sincere interest for learning.

As a first generation Canadian I can truly identify with these children. My parents were often absent as they worked long hours as they struggled to become established here in Canada. Ever since a young age I had a very strong affinity for the sciences, however I lacked the appropriate means to learn the crucial fundamentals of science as a discipline due to an absence of parental guidance. Of course, this was simply the way things were at the time as my family was in a very tight position financially.

I can also identify with these children on a patient-level. My sister was a severe asthmathic and was often whisked away in the dead of night due to episodes of attacks. In fact, she had been admitted to SickKids on numerous occassions to recieve treatment (i.e. oxygen delivery and steroid administeration). As a result, SickKids has a very special place in my family's heart and we will feel forever indebted to the medical staff and technicians who provided continual care and support for my sister in her times of need. Thus I can appreciate the effects hospitalization can have on the indiviudal (case in point my sister), as well as their family as a whole.

Finally, the patient demographic (consisting of a disproportionate number of low SES children with a foreign background) has influenced our script writing process. We have drawn on some of the principles discussed in class (Kolb's Experiential Learning) to help formualte scripts that incorporate visuals and greater hand-gestures to aid in the facilitation of knowledge aquisition amongst some of the audience members who may not necessarily have a strong command of the English language.

Evaluation Form

Above is the evaluation form that was instrumental during the script writing and script editing process. The evaluation form allowed us to gauge the quality of our performance and the effectiveness of our script, as well as providing us with the questions on which all our episodes (except the pilot of course) were based. The children proved to be quite frank with their evaluations of our performance, which allowed us to tweak our performance to better cater to them. This showed to be particularly useful during our first live-audience performance. We had clearly miscalculated the audience’s level of acquired knowledge. This proved to be disastrous and our feeble attempt to educate was nothing short of patronizing. Fortunately, the children saw this as an attempt to display their knowledge and participated vehemently. The recognition and acknowledgment the children received for their answers promoted further participation and ultimately resulted in a free-for-all in question asking. The staff and parents ensured us that the freedom for discussion and participation provided by the script had been invaluable, particularly in an environment where all aspects of the child’s life is dictated by adults and medical staff. Despite this unexpected benefit, Bushra and I had taken it upon ourselves to re-evaluate the skits, so as to make them more educational and challenging for the viewers. The skits were intended to be a learning tool through which we had hoped to disseminate knowledge to a younger generation. However, by setting the bar too low, we have allowed little room for knowledge acquisition. To prevent this from occurring, all scripts were performed in front of a test-audience consisting of children (family members) within the target age-range. Based on audience response the appropriate modifications were made. Despite this intensive re-evaluation process, we preserved the interaction component and allowed for active learning in which children were encouraged to formulate their own hypotheses and generate their own questions. The sense of control provided by this method is invaluable.

Bushra and I decided to use this form of child-friendly survey, which we had learned about in our Psychology and Research Methods course (PSYB01). The smiley faces were quite easy for the children to distinguish and were easier to comprehend than words. This also facilitated participation from younger audience members and allowed all children to feel included and provided them with a sense of responsibility. Although we had first made the evaluation form 2 pages, we decided to cut it down to a single page. This proved to be a good idea as the form seemed less tedious and increased participation amongst audience members. The evaluation forms provided us with great feedback, in retrospect the children were actually quite frank. They seemed to experience no inhibition or reservation in providing us with honest feed back, completely devoid of pleasantries and formality. This form of criticism, however had a great impact on our presentations--the rugged nature of the suggestions rung alarm bells in our heads and we were quick to make the appropriate alterations prior to our next show. Lastly, the "Wonder Why?" portion was a great addition, which we had first thought of when formulating the overarching idea of Eureka. We wanted to make our show unique and this proved to be that special added touch we needed. The children were more likely to participate and show interest during the show and were excited at the prospect that their question may be selected for our next show.

Characters

Two characters (Meinstein and Boo; see picture right) are constant throughout all the episodes, and provide a sense of continuity between the skits. Although 80% of the hospital's children change weekly, many children are admitted for long-term hospitalization. In such cases these characters provide a sense of familiarity and comfort amongst the children. Bushra and I have been approached on countless occasion by children and families alike, within the halls of the hospital, recognizing us by our stage personalities and referring to us as such. Children whom were at one time very reluctant to communicate with us, now approach us with great ease and comfort.

Two characters (Meinstein and Boo; see picture right) are constant throughout all the episodes, and provide a sense of continuity between the skits. Although 80% of the hospital's children change weekly, many children are admitted for long-term hospitalization. In such cases these characters provide a sense of familiarity and comfort amongst the children. Bushra and I have been approached on countless occasion by children and families alike, within the halls of the hospital, recognizing us by our stage personalities and referring to us as such. Children whom were at one time very reluctant to communicate with us, now approach us with great ease and comfort.

Meinstein

Grant

The Get Well Soon Grant was a project grant being awarded by Dosomething.org in collaboration with the Dunkin’ Donuts & Baskin-Robbins Community Foundation to individuals who are taking action to help children in hospitals. As I had mentioned earlier, the shows proved to be quite cost-intensive (for a budget form illustrating the costs of some of our experiments, please click the thumbnail below) and thus we had difficulty gathering the funds to have the episodes work exactly as we had envisioned them, and thus often found ourselves making modifications to our script and experiments so that they would be more financially feasible. We often used money out of our own pockets (from work and scholarships), as well as money we received from beneficiaries (i.e. parents, siblings, family members, etc). Unfortunately, I was not awarded the grant, but used the process as a learning experience when applying for other grants (i.e. Seed Grant award by Dosomething.org--results have yet to be posted). It is worth mentioning that grant winners were selected by a voluntary panel of judges who are part of the Dosomething community. As a result, many of the winners simply invited all of their friends on facebook to sign-up as members of Dosomething.org--by completing a simple application form--and become part of the voluntary pool of judges. This may explain why we were beat out by groups like the "hugs for children" campaign which really has no financial expenditure attached to it.

I had never applied for a grant in the past. This experience allowed me to understand the grant writing process. It also allowed forced me to gain a deeper understanding of Eureka Science during its infant stages. I was forced to think of things I had at first failed to consider. We had been concentrating so strongly on our pilot episode, that we lost sight of the future. The grant process forced me to consider the future of Eureka, what it was and what it would become. The grant actually resulted in the incorporation of many of the ideas that make Eureka Science what it is. For instance, it was through this process we decided to introduce the child-friendly surveys to map our progress, have the "Wonder Why?" section, and gain a greater understanding of the financial expenditure required per an episode (please see enclosed the Grant Budget Form above, this budget form was created for a grant I had more recently applied for).

Characters

Two characters (Meinstein and Boo; see picture right) are constant throughout all the episodes, and provide a sense of continuity between the skits. Although 80% of the hospital's children change weekly, many children are admitted for long-term hospitalization. In such cases these characters provide a sense of familiarity and comfort amongst the children. Bushra and I have been approached on countless occasion by children and families alike, within the halls of the hospital, recognizing us by our stage personalities and referring to us as such. Children whom were at one time very reluctant to communicate with us, now approach us with great ease and comfort.

Two characters (Meinstein and Boo; see picture right) are constant throughout all the episodes, and provide a sense of continuity between the skits. Although 80% of the hospital's children change weekly, many children are admitted for long-term hospitalization. In such cases these characters provide a sense of familiarity and comfort amongst the children. Bushra and I have been approached on countless occasion by children and families alike, within the halls of the hospital, recognizing us by our stage personalities and referring to us as such. Children whom were at one time very reluctant to communicate with us, now approach us with great ease and comfort.Meinstein

Meinstein is the character I play. He is meant to embody all things science, while fitting the stereotype of the eccentric, clumsy, mad-scientist fully-equipped with a strange, indistinguishable foreign accent. Although clearly the adult figure in the skit, he is the target of many jokes within the series, particularly pertaining to his potent body odor and infatuation with eating goo. Meinstein was incorporated into our skit in order to aid in the abolishment of some of the fears and insecurities that may plague the children when dealing with adults in white coats (particularly the medical staff). An inquisitive little girl Boo (played by Bushra) innocently pokes fun at Meinstein and proves to be just as scientifically competent, while expressing a quiet respect for Meinstein as an adult. Thus, the colloquial exchanges between the two characters attempt to "break the ice" between the children and medical staff, by illustrating scientists and children can interact in an amicable manner.

Boo

Boo is the inquisitive, little girl played by Bushra Rizwan (my partner). She always enters the laboratory abruptly with a handful of mail from our viewers and is responsible for reading out the question posed by our audience members. She then participates in the explanation process, carries out her own experiments, and corrects Professor Meinstein's mistakes. She continuously exceeds Professor Meinstein's expectations and proves her competence as a scientist. Boo (inspired by the little girl from Monster's Inc) was introduced to empower the children in the audience. The children can easily relate to a character that is supposed to be within their age range. The intelligence expressed by Boo seems to diffuse over to the audience, and ignite a sense of capacity within the young audience members encouraging further involvement. In fact, a very interesting trend can be seen during presentations. Children often remain quite reserved and do not willingly respond to questions--often requiring prompts or encouragement from parents and staff. It is only when Boo pops into the lab and exchanges insight with Professor Meinstein and makes a few witty remarks, the children begin to feel more comfortable participating. It seems that viewing another "child" providing their opinion relinquishes some of the inhibitions the children may be experiencing and opens the flood gates for further participation.

Special Guests

These are special characters I play that appear on a single episode in order to explain a particular scientific principle. These individuals tend to be characters the children are familiar with via Disney movies or pop-culture. The characters are selected for an episode based on their relevance to the scientific concept being examined (i.e. the Evil Queen from Snow White (see photo left) was used to explain the physics behind mirrors, due to her pathological obsessions with her image--which she viewed through a magical mirror).

Playing Meinstein and the different guests on the show proved to be an enjoyable experience and a great test of my acting ability (which before this show was completely non-existent). Over time, and after watching hundreds of hours of Spongebob, I gained a greater understanding of what jokes and actions interested the children. Eccentricity and foreign accents seemed to elicit laughter and giggles from the crowd of children. We also threw some jokes in that would appeal to an older audience, without offending anyone (we hope). However, we were careful not to go overboard and were sure to maintain an air of seriousness, particularly when getting explaining important scientific concepts. The costumes we assembled a week in advance. The characters seemed to provide a degree of familiarity for the children and the different characters also provided a comfortable level of variability between performances. I truly enjoyed acting as different characters and giving a comical twist to their personas. I had the liberty to play the characters as I wished (although often being told to tone it down by Bushra) and used the script as a guideline. We often improvised and this seemed to produce the most enjoyable episodes, often producing comical situations that weren't at first intended to be funny (i.e. forgetting to plug-in a blender, getting hit by a rocket (which we later used as a lesson in safety), etc).

Junior Scientist Certificate

Activity Sheets

Activity sheets (please click to enlarge) were used as placeholders for all the meal trays being delivered to the various hospital rooms, as well as to those patients eating in the cafeteria. They served a dual purpose, they promoted our show and listed the date, time, channel, and location of our show, as well as informed our audience of the theme for that week's episode.

Special Guests

These are special characters I play that appear on a single episode in order to explain a particular scientific principle. These individuals tend to be characters the children are familiar with via Disney movies or pop-culture. The characters are selected for an episode based on their relevance to the scientific concept being examined (i.e. the Evil Queen from Snow White (see photo left) was used to explain the physics behind mirrors, due to her pathological obsessions with her image--which she viewed through a magical mirror).

Playing Meinstein and the different guests on the show proved to be an enjoyable experience and a great test of my acting ability (which before this show was completely non-existent). Over time, and after watching hundreds of hours of Spongebob, I gained a greater understanding of what jokes and actions interested the children. Eccentricity and foreign accents seemed to elicit laughter and giggles from the crowd of children. We also threw some jokes in that would appeal to an older audience, without offending anyone (we hope). However, we were careful not to go overboard and were sure to maintain an air of seriousness, particularly when getting explaining important scientific concepts. The costumes we assembled a week in advance. The characters seemed to provide a degree of familiarity for the children and the different characters also provided a comfortable level of variability between performances. I truly enjoyed acting as different characters and giving a comical twist to their personas. I had the liberty to play the characters as I wished (although often being told to tone it down by Bushra) and used the script as a guideline. We often improvised and this seemed to produce the most enjoyable episodes, often producing comical situations that weren't at first intended to be funny (i.e. forgetting to plug-in a blender, getting hit by a rocket (which we later used as a lesson in safety), etc).

Junior Scientist Certificate

This certificate is awarded to children after attending an episode of Eureka Science, it was inspired by the certificates received by Bushra's younger cousin (in grade 3). We realized that her younger cousin had received an array of certificates for a variety of activities, and oddly these deceivingly simple sheets of paper had a large and real impact on her future behaviour. Reinforcement through award appeared to go a long way and promoted further participation and positive feelings of self-content and accomplishment. We decided to incorporate this award into our presentation and found that it had a very strong and powerful effect on our audience. Many of the children informed us they had never received an award before and showed great excitement upon having their names signed and being given the title of "Junior Scientist". This simple addition to our skit had an equally strikingly effect on the parents who were, on more than one occasion, drawn to tears. Observing the excitement and happiness being experienced by their children, often after days of turmoil, was very emotionally moving for the parents, as well as for Bushra and I.

Activity Sheets

Grant

The Get Well Soon Grant was a project grant being awarded by Dosomething.org in collaboration with the Dunkin’ Donuts & Baskin-Robbins Community Foundation to individuals who are taking action to help children in hospitals. As I had mentioned earlier, the shows proved to be quite cost-intensive (for a budget form illustrating the costs of some of our experiments, please click the thumbnail below) and thus we had difficulty gathering the funds to have the episodes work exactly as we had envisioned them, and thus often found ourselves making modifications to our script and experiments so that they would be more financially feasible. We often used money out of our own pockets (from work and scholarships), as well as money we received from beneficiaries (i.e. parents, siblings, family members, etc). Unfortunately, I was not awarded the grant, but used the process as a learning experience when applying for other grants (i.e. Seed Grant award by Dosomething.org--results have yet to be posted). It is worth mentioning that grant winners were selected by a voluntary panel of judges who are part of the Dosomething community. As a result, many of the winners simply invited all of their friends on facebook to sign-up as members of Dosomething.org--by completing a simple application form--and become part of the voluntary pool of judges. This may explain why we were beat out by groups like the "hugs for children" campaign which really has no financial expenditure attached to it.

I had never applied for a grant in the past. This experience allowed me to understand the grant writing process. It also allowed forced me to gain a deeper understanding of Eureka Science during its infant stages. I was forced to think of things I had at first failed to consider. We had been concentrating so strongly on our pilot episode, that we lost sight of the future. The grant process forced me to consider the future of Eureka, what it was and what it would become. The grant actually resulted in the incorporation of many of the ideas that make Eureka Science what it is. For instance, it was through this process we decided to introduce the child-friendly surveys to map our progress, have the "Wonder Why?" section, and gain a greater understanding of the financial expenditure required per an episode (please see enclosed the Grant Budget Form above, this budget form was created for a grant I had more recently applied for).

LORs (Letters of Recommendation)

Above you will find the Letters of Recommendation (LORs--please click to enlarge) provided to me by my placement supervisor (at the time Susie Petro--Ms.Irwin was away on maternity leave), Adnan Syed (VoSNL), and Dr. Kamini Persaud (U of T, Scarborough Campus). Although I did not receive the Get Well Soon Grant, these letters have played an important role in pushing me as a performer and scientist. I must admit there were times at which I felt I may not be appropriately qualified to teach younger children (functioning as an initial gate-keeper to the world of science) and began to second-guess whether my work was of the right caliber. I often wonder if this project would be better managed and presented by another group of individuals (perhaps MSc students, PhD candidates, medical residents, actors, etc). However, when I read over these letters I feel capable and garner a sense of empowerment--three individuals, whom I hold in high regard, have rendered me competent and feel I can put on a good show for these youngsters. These letters have served more than their initial purpose, it is through them I find the strength to pursue what we had first sought out for--a more science literate/savvy and happier SickKids.